In October I sketched a detail of this Dürer woodcut to scale and carved it on linoleum with a woodcut knife to learn the process and see if I like it. The carving took longer than I expected, but was surprisingly enjoyable, more meditative than painting. So here is my first print ever.

My second experiment was an attempt at a chiaroscuro woodcut. Wood is more fun, I noticed that the grain made me want to stylise and exaggerate while drawing (which gave the figs a sea-creature look).

|

| freehand copy after "St. Christopher" by Dürer Lala Ragimov, 2012 |

My second experiment was an attempt at a chiaroscuro woodcut. Wood is more fun, I noticed that the grain made me want to stylise and exaggerate while drawing (which gave the figs a sea-creature look).

|

| Lala Ragimov, 2012 |

***

The question I had right away was what were the tools used by Renaissance printmakers and how were they handled, to be able to find similar modern tools to use. I saw a lot of information online on how to make a Japanese woodblock print but almost none on how to make a Renaissance woodcut, so I looked at these:

"The Renaissance Print: 1470-1550" (1994) by D. Landau and P. Parshall (limited view here)

"Traité historique et pratique de la gravure en bois" (1766) by J.-M. Papillon (free here)

"An Introduction to a History of Woodcut" (1935) by A. Hind

"Über die Technik des alten Holzschnittes" (1890) by S. R. Koehler (free here) and his comparison of Japanese and Renaissance techinques here ("Japanese wood-cutting and wood-cut printing", 1894)

"The Renaissance Print: 1470-1550" (1994) by D. Landau and P. Parshall (limited view here)

"Traité historique et pratique de la gravure en bois" (1766) by J.-M. Papillon (free here)

"An Introduction to a History of Woodcut" (1935) by A. Hind

"Über die Technik des alten Holzschnittes" (1890) by S. R. Koehler (free here) and his comparison of Japanese and Renaissance techinques here ("Japanese wood-cutting and wood-cut printing", 1894)

- "The Renaissance Print" lists the tools: a pointed knife (to carve the outlines), and flat and round chisels (to remove remaining wood). This was deduced from the tool marks on surviving blocks. The wood types most frequently mentioned are pear and boxwood. The planks were usually covered with a white ground, the drawing was transferred or glued on (or drawn directly on the plank) and carved.

- This woodcut (1568) by Jost Amman shows a knife with a slanted cutting edge. The woodcutter's frilly trousers must be perfect for collecting wood shavings.

|

| Jost Amman Der Formschneider 1568 |

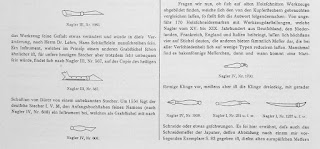

- In his 1766 treatise Papillon advises boxwood, service tree, wild and cultivated pear, apple and cherry. He suggests pear wood to beginners. He has an entertaining illustration of historic (2-15) and Asian (1) knives that he criticises as uncomfortable and dangerous. No.13 is described as the one most frequently seen in old monograms.

|

| Jean-Michel Papillon |

- These are illustrations of his own knife, how to shape it for various needs and how to handle it. It has a straight cutting edge with a bevel, and a slanted opposite edge (description here).

|

| Jean-Michel Papillon, 1766 |

- Koehler shows more shapes redrawn from monograms. He says most depictions show a straight or a slightly curved cutting edge (the two knives at bottom right).

|

| Koehler 1890 |

- For comparison Japanese block prints are made mostly on sakura (wild cherry) wood. The drawng is pasted on and its outlines are carved with a knife with a slanted cutting edge and one bevel.

| A hangi-to woodblock knife image source David Bull's site |

To sum up, it looks like most Renaissance knives had a slanted, curved or straight cutting edge. Most had a structure that allowed gripping them close to the tip, like a pen (like in Amman's and Papillon's illustrations of the process).

Modern woodcut knives I've seen (Japanese and Western) need to be held differently because of their longer blades. So the most similar instrument I can think of is the regular pen-like X-acto knife, which I will try next time.

Modern woodcut knives I've seen (Japanese and Western) need to be held differently because of their longer blades. So the most similar instrument I can think of is the regular pen-like X-acto knife, which I will try next time.

Bevel questions:

1) It seems (if I understood right) that Papillon carved with the knife bevel facing the print line, but what I read here for Japanese knives is that the bevel side compacts and damages the wood. Did Papillon not have that problem? Is it a problem for everyone?

2) I'm curious if there is a more detailed description of a Renaissance woodcut knife and its bevels. Parshall does say that the knife had one bevel and refers to a picture in "An Introduction to a History of Woodcut" by A. Hind. I got enthusiastic and found it, but it's only a modern drawing of a generic Japanese-looking tool. Hind says that the knife had one bevel, on the opposite side to that of a Japanese knife, but he doesn't say why he thinks so, so I feel like it could be a guess.

©Lala Ragimov

no artwork or text by Lala Ragimov may be reproduced without permission of the author.

1) It seems (if I understood right) that Papillon carved with the knife bevel facing the print line, but what I read here for Japanese knives is that the bevel side compacts and damages the wood. Did Papillon not have that problem? Is it a problem for everyone?

2) I'm curious if there is a more detailed description of a Renaissance woodcut knife and its bevels. Parshall does say that the knife had one bevel and refers to a picture in "An Introduction to a History of Woodcut" by A. Hind. I got enthusiastic and found it, but it's only a modern drawing of a generic Japanese-looking tool. Hind says that the knife had one bevel, on the opposite side to that of a Japanese knife, but he doesn't say why he thinks so, so I feel like it could be a guess.

|

| from A. Hind, 1935 |

©Lala Ragimov

no artwork or text by Lala Ragimov may be reproduced without permission of the author.

My other posts on topics related to technical art history

Inspired

by Rubens (Getty Museum page)

Copying a Rubens drawing (materials, techniques)

Copying a Rubens painting (materials, techniques)

Copying a Rubens drawing (materials, techniques)

Copying a Rubens painting (materials, techniques)

1400s-1700s drawing

treatises online

Painting materials of Rubens; bibliography

Renaissance woodcut tools

Image gallery: my copies and reconstructions

Painting materials of Rubens; bibliography

Renaissance woodcut tools

Image gallery: my copies and reconstructions

Fascinating Lala. As someone who dabbles in print-making occasionally it is interesting to hear about the historical approaches to this medium.

ReplyDeleteThank you Sarah!

ReplyDeletenice post!!! we have this post of our shop. you can visit of of our site.visit woodcarvingarts.webs.com

ReplyDelete